Now Playing

Current DJ: Sarah Spencer

David Lynch Wishin' Well from The Big Dream (Captured Tracks) Add to Collection

Requests? 773-DJ-SONGS or .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

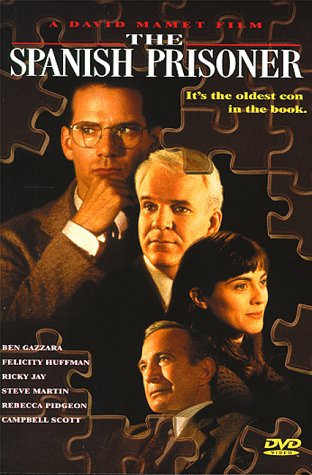

Welcome to The Fourth Wall, CHIRP's e-conversation on cinema. This week's subject is the 1997 film The Spanish Prisoner.

This edition is written by CHIRP Radio volunteers Kevin Fullam and Clarence Ewing.

Kevin:

The Big Con. It's long been a favorite cinema staple of mine. You can't sleepwalk through Big Con films -- you gotta keep your eyes and ears peeled at all times, and definitely, absolutely trust no one. As an added bonus, the Everyman protagonists of these tales are usually in the dark as much as the audiences, making them the perfect proxy. We're attached at the hip and invested from the get-go.

In David Mamet's The Spanish Prisoner, Joe Ross (Campbell Scott, whose muted temperament is the perfect fit for this sort of role) has created a "Process." Manifested as a notebook of charts and formulas, it's a classic MacGuffin -- we have no idea what it exactly involves, except that it's worth astronomical sums of money to the company which employs him... or to anyone else who winds up getting a hold of it.

While on the island of St. Estèphe to discuss the Process with company investors, Ross rubs elbows with new secretary Susan Ricci (Rebecca Pidgeon, Mamet's real-life wife) and wealthy traveler Jimmy Dell (Steve Martin), the latter of whom eases himself into Joe's world by giving him a package to "deliver to his sister in New York." Worried it might be something illegal, Joe opens the package -- which is revealed to be an innocuous 1930s book about tennis.

Right around this time, relations between Joe and his employers turn frosty, and he starts to fret about not receiving fair compensation. Jimmy (having reconnected in the Big Apple) suggests enlisting outside legal counsel. Can he trust him? What about Susan? And later there's an FBI team (headed by Ed O' Neill) involved in the case as well. But are they actually federal agents? Just when exactly does the con stop... or is it still going when the credits start rolling?

written by Kyle Sanders, reporting from the 58th Chicago International Film Festival

Barely a week through the Chicago International Film Festival, and I feel as if I'm slacking! Then again, my goal for reviewing films this year was supposed to involve a little organization, but as any press accredited film critic would probably tell me, watching festival flicks in the order of my choosing would NOT go so smoothly. That being said, I'm four films in, and while they aren't exactly how I'd planned to watch them, these films share more similarities than I initially gave them credit for...

Art and Pep

First things first, a Chicago-oriented documentary about one of Chicago's popular gay bars owned by a pair of Chicago activists: Art and Pep (U.S.). Since opening Sidetrack in 1982, Art Johnston and Pepe Pena had the goal of creating a welcoming space for the gay community of Northalsted (formerly known as Boystown). They had no idea it would become a haven of joy and solidarity through 40 tumultuous years, with its humble beginnings during the AIDS crisis and persevere through the uncertainty of the Covid pandemic. In between that time, they found themselves becoming local civil rights leaders, co-founding Equality Illinois while expanding their meager bar into an iconic Chicago establishment.

Alvvays – Blue Rev (Polyvinyl/Transgressive)

This summer I read an enlightening biography on the late Pauline Kael (A Life in the Dark for those interested), one of the most influential and provocative film critics of the twentieth century. She climbed her way up through the ranks (as a working single mother no less!) to claim her throne at The New Yorker where she reigned for nearly twenty-five years.

This summer I read an enlightening biography on the late Pauline Kael (A Life in the Dark for those interested), one of the most influential and provocative film critics of the twentieth century. She climbed her way up through the ranks (as a working single mother no less!) to claim her throne at The New Yorker where she reigned for nearly twenty-five years.

What's interesting is that her approach to reviewing cinema involved no technological prowess or scholarly theory on the art form--it was all emotion. Watching a film meant undergoing a transformative experience; to Kael, it was personal.

Kael's tenure at The New Yorker ended in 1991 when I was much too young to connect with her biting reviews. By the time I learned of her significance in film criticism, she had already passed away in 2001. But finishing her biography left me with the impression that her influence still lingers, because I realize her sensibilities toward cinema march in unison with my own: I no longer yearn for a film to entertain me, I want to feel it.

That wish is granted every October during the Chicago International Film Fest. In it's 58th year (and my SIXTH year of CHIRP coverage), CIFF brings over ninety features and sixty short films to the Windy City, ranging from life-affirming dramas to eye-opening documentaries and midnight shockers.

by Features Contributor DJ Ninja

by Features Contributor DJ Ninja

Chicago musician Al Rose talks 8th album, future-proofing protest songs, and a storied flute history

Despite flute being the first instrument that Chicago musician Al Rose picked up at age 10, he doesn’t play it on stage anymore. He played in the school band, was classically trained. But no more on stage.

“I used to play flute more often in the early part of my career, but I got tired of drunk people in particular shouting out ‘Tull!’ every time I picked up the flute,” Rose said. “I mean, don't get me wrong. I really do like Jethro Tull. But I got tired of people going ‘TUUULL!’ It's kind of the flute version of ‘Freebird.’”

Rose focuses these days on the acoustic guitar as his primary instrument at gigs, and he occasionally plays electrics when recording in the studio, including a 12-string Rickenbacker on his latest album, “Again the Beginner.” But he still picks up other instruments from time to time.

“I do harmonica at some of the live shows,” Rose said. “I have been teaching myself mandolin over the last couple of years but have not had the courage to play it in front of people yet.”